‘My Mass

will be quite different from all the rest…I will show people how to talk to

God.’

Leoš Janáček

Setting modest goals was clearly out of the question

for Janáček as he wrote the Glagolitic Mass in his final decade. Already

enjoying considerable success from his recent operatic works (Kát’a Kabanová (1919-21), The Cunning Little Vixen (1921-3) and The Makropulos Affair (1923-5), Janáček

relied upon his international renown when taking the risk of writing a large-scale

liturgical composition, a genre that was declining in popularity in

Czechoslovakia in the 1920s.

That being said, the Glagolitic Mass was well-received

and written about widely. One of the most

fascinating pieces of literature, however, is Janáček’s own article in Lidové noviny,

a popular daily newspaper published in Prague, which continues to be

successful today as one of the Czech Republic’s longest-standing publications.

This article, taking the form of a lengthy poem about the Glagolitic Mass,

seeks to explain the compositional process, as well as to express the context

of its inception. Yet the complex contextual factors contributing to and the

agendas shaping the composition of the Mass can be discovered by reading this

poem considering alternative evidence to Janacek’s writings alone. Using quotations

from the poem, I will explore some of the factors affecting the composition

process and its reception.

Below is Wingfield’s (1992) translation of the poem in full

and following that my discussion of some of the key points arising from Janáček’s poem.

Why did I compose

it?

It pours, the

Luhačovice rain pours down. From the window

I look up to the glowering Komoň mountain.

Clouds roll past;

the gale-force wind tears them apart, scatters them far and wide.

Exactly like a month ago: there in front of the Hukvaldy school we

stood in the rain.

And next to me the high-ranking ecclesiastical dignitary

[Archbishop Prečan].

It grows darker and

darker. Already I am looking into the black night; flashes of lightning cut

through it.

I switch on the flickering electric light on the high ceiling.

I sketch nothing more than the quiet motive of a desperate frame of

the mind to the words

‘Gospodi pomiluj’. [Lord have mercy]

Nothing more than the joyous shout ‘Slava, Slava!’ [Glory].

Nothing more than

the heart-rendering anguish in the motive ‘Rozpet že za ny, mŭcen I pogreben jest!’ [and was crucified also for us,

he suffered and was buried].

Nothing more than

the steadfastness of faith and the swearing of allegiance in the motive

Vĕruju!’ [I believe].

And all the fervour and excitement of the expressive ending

‘Amen, Amen!’.

The holy reverence in the motives ‘Svät, svät!’ [Holy],

‘Blagoslovjen’ [Blessed] and ‘Agneče Božij!’ [O Lamb of God].

Without the gloom of medieval monastery cells in its motives,

without the sound of the usual imitative procedures,

without the sound of Bachian fugal tangles,

without the sound of Beethovenian pathos, without Haydn’s

playfulness;

against the paper barriers of Witt’s reforms - which have estranged

us from Křížkovsky.

Tonight the moon in

the lofty canopy lights up my small pieces of paper full of notes -

tomorrow the sun

will steal in inquisitively.

At length the warm

air streamed in through the open window into my frozen fingers.

Always the scent of

the moist Luhačovice woods - that was the incense.

A cathedral grew

before me in the colossal expanse of the hills and the vault of the sky,

covered in mist into the distance; its little bells were rung by a flock of

sheep.

I hear in the tenor solo some sort of a high priest,

in the soprano solo a maiden-angel,

in the chorus our people.

The candles are high

fir trees in the wood, lit up by stars; and in the ritual somewhere out there I

see a vision of the princely St Wenceslas.

And the language is

that of the missionaries Cyril and Methodius.

1.

Exactly like a month ago: there in front of the Hukvaldy school we

stood in the rain.

And next to me the high-ranking ecclesiastical dignitary

[Archbishop Prečan].

With

the divide between sacred and secular music deepening throughout Europe at the

time of this work’s creation, the most important feature of sacred choral music

composition had become liturgical functionality. Stemming from Cecilian

principles, the Cyrillian movement promoted

a return to polyphonic choral music inspired by the sixteenth century.

According to Wingfield, these influences took hold in the Catholic Church in

Czechoslovakia from the early 20th century, and they are clearly

present in the text of the Glagolitic Mass, which, being written in Old Church

Slavonic, has clear links to the patriotic research practices of scholars inspired

by Cecilian and Cyrillian principles. Janáček had engaged in multiple discussions

with Archbishop Prečan about the composer’s dislike of the quasi-renaissance of

Czechoslovakian choral church music, in which the Archbishop is rumoured to have

challenged the composer to write a grand mass setting (Wingfield 1992).

Yet Janáček’s apparent reverence of ‘the high-ranking

ecclesiastical dignitary’ must be considered in the light of the composer’s atheism;

the concept of ‘teaching people how to talk to God’, or indeed even writing for

liturgical purposes, demonstrates a somewhat artificial relationship between the

composer’s choice of genre when composing the Glagolitic Mass and his true opinions of the Church and the higher purpose of sacred music.

2.

I switch on the flickering electric light on the high ceiling.

I sketch nothing

more than the quiet motive of a desperate frame of the mind

Throughout

his poem, the composer paints a rather romanticised version of his composition

process; sitting alone, in the countryside in stormy weather, with little

electricity and a pen and paper, one could not possibly infer that he had

already written the central melodic content for at least one of the movements

twenty years earlier for a group of composition students. Originally titled ‘Latin

Mass’, Janáček’s first attempt at writing a Mass setting was for a class

in the early 1900s, and much of the music he wrote to instruct his students on how

to compose sacred music has been repurposed for the Glagolitic Mass. The

composer, upon writing the Glagolitic Mass, destroyed all evidence of the

original, the only extant evidence of which can be found in the transcriptions

of Vilém Petrželka, who was one of his students at

the Brno Organ School in 1908. (Wingfield, 1992). Indeed, so indebted was his compositional

process to these original musical ideas that the process of writing the first

draft took a mere ten days. The ‘quiet motive’ inspired by the stormy surroundings

in 1927 had already been fully formed nearly twenty years earlier, however the

composer’s desire to present his inspiration as being linked to nature and the

divine is undeniable and consistent throughout the poem; perhaps Janáček sought through this publication to confirm his

status as an internationally celebrated composer by removing any discussion of

reused material.

3. Nothing more than

the joyous shout ‘Slava, Slava!’

Janáček’s devotion to the religious text is

asserted several times during the poem, and this raises some important issues

surrounding his treatment of the text. Taking ‘Slava’ (Gloria) as an example, one sees evidence in the musical structure of the careful consideration

taken when setting the text. The standard Gloria text is given a bipartite

structure, being subdivided into eight, in turn divided into 5 and 3 musical

sections in accordance with the lines of the Gloria text, in order to create a

musical partition between the glorifying of the Father and the Son in the text.

Ethereal harmonics in the violin parts are combined with joyful ‘shouts’ in the soprano line, alternating

tonal centres, and regularly changing tempo markings, to create a constantly evolving movement in

which variants of the opening motives recur, just as the text repeats with

minor changes throughout.

Yet

the composer’s many revisions of the text (including changing the Old Church

Slavonic’s vowel constructions in some cases for ease of singing) demonstrates

that this apparent faithfulness to the liturgical content of the work was accompanied by his

aesthetic approach to composition (Culver,2005). This directly opposed the text-first

approach to composition found in much sacred music of the time, instead favouring the wide range of sentiments found within

the Mass and their potential for musical expressivity, including the ‘fervour

and excitement of the expressive ending’, over the importance of the liturgical

text and the correct transcription of the language and the performance thereof (Holloway, in Wingfield, 1999). Despite the implied reverence to the liturgical text, Janáček’s

preference for using the Glagolitic alphabet (an early Slavic alphabet) was clearly

linked to his compositional focus on the expressive, non-religious element of

the text (Langston, 2014). This premise is supported by the notes of Petrželka, who quotes the

composer as saying ‘Write Latin, think Czech’ when teaching sacred composition,

an idea which clearly endured throughout the composer’s life (Wingfield, 1992).

4. Without the gloom of medieval monastery cells in its motives,

without the sound of

the usual imitative procedures,

without the sound of

Bachian fugal tangles,

without the sound of

Beethovenian pathos, without Haydn’s playfulness;

against the paper

barriers of Witt’s reforms - which have estranged us from Křížkovsky.

Distancing

himself from the traditions of canonic composers such as Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, and demonstrating a clear preference for Czech composer and conductor Pavel Křížkovsky, the composer here seeks to prepare his

audience just before the premiere through his publication for the overt musical influences of previous Czech composers rather than those

more typically found in the Austro-Germanic classical tradition. Interestingly,

Křížkovsky’s compositional output centred upon bringing choral settings of folk

songs and sacred vocal music to the concert hall in Czechoslovakia. By

referencing Křížkovsky in his poem, Janáček draws

clear parallels between his predecessor’s work and his own attempts to bring a sacred

Mass inspired by Old Church Slavonic and Cyrillic philosophies to the concert

hall in 1927. This reference, whilst demonstrating the aims of the composer’s writing

process, also seems to be an attempt to justify the artistic choices of using a

less popular genre of music at the time, by bringing publicity and authority to

the large-scale form through comparing it to the successful output of a Czechoslovakian

composer of the nineteenth century. (Encyclopedia of Brno Online.)

5.

I hear in the tenor solo some sort of a high priest,

in the soprano solo

a maiden-angel,

in the chorus our

people.

The

reception of the work was largely appreciative and uncontroversial; hailed by

William Ritter as ‘a revelation’ shortly after its premier, and then later in

his 1928 article in the Gazette de

Lausanne as being unmatched in contemporary composition. Much of this had

to do with the composer’s own expression of the work’s nationalistic

tendencies, presenting the work in an interview for Literárni svĕt as a celebration of Czechoslovakia’s independence

from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By suggesting that the chorus of the work is

intended to embody ‘our people’, Janáček sets up the work to connect with the

local audience in Czechoslovakia.

This,

whilst also demonstrating one of the reasons for the work’s creation, also

creates a conflicting perspective to that set up in the beginning of the poem

when the composer discusses admiringly the conversation with the Archbishop;

this poem is intended to appeal to all, regardless of religious position, and enables

the composer to present himself as not only more tolerant of religion and its

music than his strong atheist views might truly have permitted. It is also

designed to present Janáček as a socially relevant

and politically-driven nationalist composer who was reviving through this work

the heritage of past Czechoslovakian composers and refuting the legacy of Austro-Germanic

romanticism. The composer’s agendas demonstrate the many ways in which a

composer during this post-War period might have to justify unconventional

compositional choices, and they also demonstrate the ways in which having the renown

enjoyed by Janáček in the final decade of his life meant that making compromises

in certain artistic decisions (including modifying the text and therefore rendering

it completely impractical for liturgical performance) in order to generate a

piece which would appeal to audiences from a range of religious, social and

political backgrounds.

Bibliography

Birnbaum,

H. (1981). 'Eastern and Western Components in the Earliest Slavic Liturgy.' in

Essays in Early Slavic Civilisation. Munich.

Culver, C.

(2005) Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass is

useless". https://www.christopherculver.com/languages/janačeks-glagolitic-mass-is-useless.html.

Accessed 31/01/18.

Encyclopedia

of Brno. Pavel Křížkovsky. Accessed 31/01/18. http://encyklopedie.brna.cz/home-mmb/?acc=profil_osobnosti&load=207

Langston,

K. (2014). Janáček’s Glagolitic mess: Notes

on the text of the Glagolitic Mass and pronunciation guide. UGA Dept. of

Germanic and Slavic Studies. Accessed 31/01/18.

Steinberg, M. (2008). Choral masterworks: a listener's guide. Oxford;

New York: Oxford University Press

Wingfield,

P. (1992). Janácek, Glagolitic mass (Cambridge music handbooks). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Wingfield,

P. (eds.) (1999). Janáček Studies.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zemanová,

M. (1989). Janáček's Uncollected

Essays on Music. London.

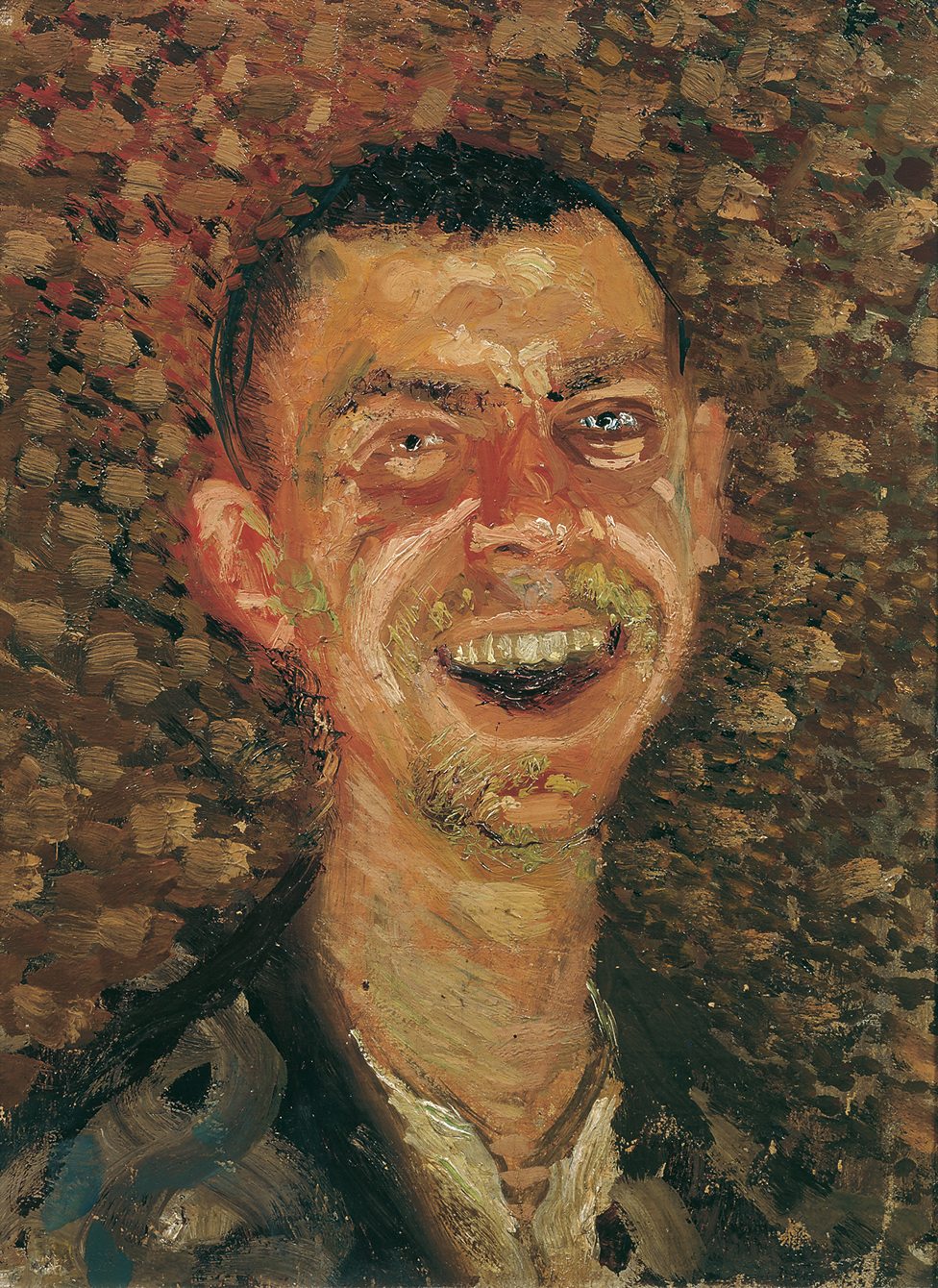

Image Source:

http://www.czechmusic.org/osobnosti.-6.vy_17.en

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/A-1926734-1347797443-2924.jpeg.jpg)